All technical disciplines have their own set of nomenclature and definitions. For example, I wouldn’t expect a geologist to have much understanding of a conversation with an aeronautical engineer about a wing’s aspect ratio or lift-to-drag ratio any more than the aeronautical engineer would have much understanding of a discussion of the late Cambrian period.

As shooters and hunters, we definitely have our own set of nomenclature that applies to our passion. Try having a discussion with your wife about the merits of a high ballistic coefficient (BC) bullet and the benefits to its trajectory, retained velocity and terminal performance for the big-game hunter. How long did it take for her eyes to glaze over? Along those lines, I thought it might be beneficial to readers to review several ballistics terms, what they mean and how they can be used to help hunters make choices about what bullet to hunt with, how to set up a rifle and scope accordingly, and what to expect for performance in the field. I would like to delve into BC, sectional density (SD), maximum point-blank range (MPBR) and minimum striking energy (MSE). We’ll look at the definitions of these terms and consider how they can be used to guide our decisions about bullet selection and setting up a rifle and scope.

Ballistic Coefficient (BC)

I won’t go into the mathematical definition of “BC.” I have done this in detail in previous columns, first in May 2018. BC is simply the comparison of a bullets’ rate of velocity loss as it flies through the air compared to a standard bullet. The rate of velocity loss of the standard bullet has been carefully measured, and BC is a measure of how well or poorly this example bullet retains velocity compared to the standard bullet. Don’t get wrapped around the axle on whether to use “G1,” “G7,” or “whatever” BC. That tangent can lead to a lot of minutiae. Suffice it to say, if you are a traditional hunter and hunt at ranges within 400 yards, G1 will work just fine for you. If you are a long-range hunter and shoot at ranges in excess of 400 yards, you might want to be looking at G7 BC numbers.

In all cases, the higher the BC number, the better the bullet is at retaining velocity. This means the bullet shoots flatter, drifts less in the wind and retains more striking energy by the time it reaches its target. The longer the range, the greater importance BC has. The real-world bottom line is the differences in trajectories will be meaningless at normal hunting ranges unless you have a huge difference in BC. For long-range shooting, you’re going after every advantage you can reap for a flatter trajectory and reduced wind drift. As I see it, the real advantage of a higher BC bullet is the higher retained velocity, which results in greater range for effective terminal performance.

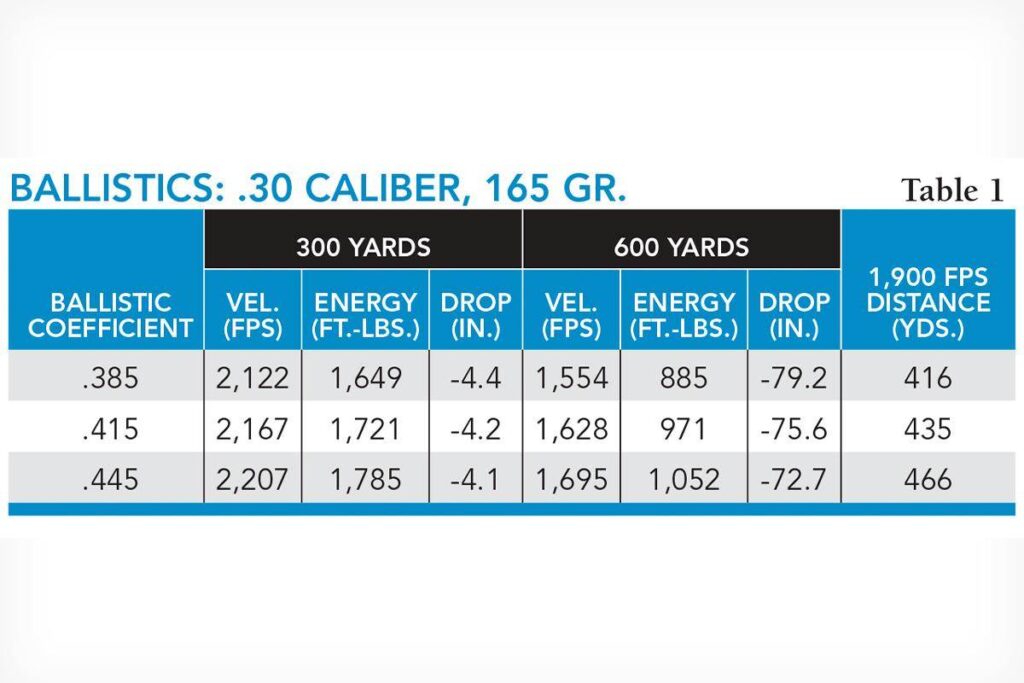

Table 1 shows the 300- and 600-yard retained velocity, energy, drop and the range that it has dropped to 1,900 feet-per-second (fps) retained velocity for a .30-caliber 165-grain bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2,800 fps and 250-yard zero with several different BCs. As you can ascertain from the table, the higher BC bullet has more retained velocity, more energy and less drop. If we say this bullet type has an expansion threshold velocity of 1,900 fps, the higher BC offers an extra 50 yards of effectiveness versus the lower BC bullet.

Sectional Density (SD)

Sectional density (SD) is a fairly simple concept. The mathematical definition of “SD” is bullet weight (gr.) divided by bullet diameter2. The useable formula is: Weight (gr.)/7000/diameter2 (in.). In practical terms, the real use of SD is that it is a round-about way of defining how long the shank of a bullet is and it is an indicator of penetration potential. Take .30-caliber hunting bullets: They are all limited to approximately the same ogive length because of the head height and magazine length of the .300 Winchester Magnum. This is the lowest common denominator for the bullet designer. The only way to get a heavier, higher SD is to have a longer shank on the bullet. The longer the shank, the heavier it is, which means the more retained weight it will have, leading to higher penetration. SD gives you an idea of what to look for in a bullet depending on the size of the game you are after and how much penetration you need.

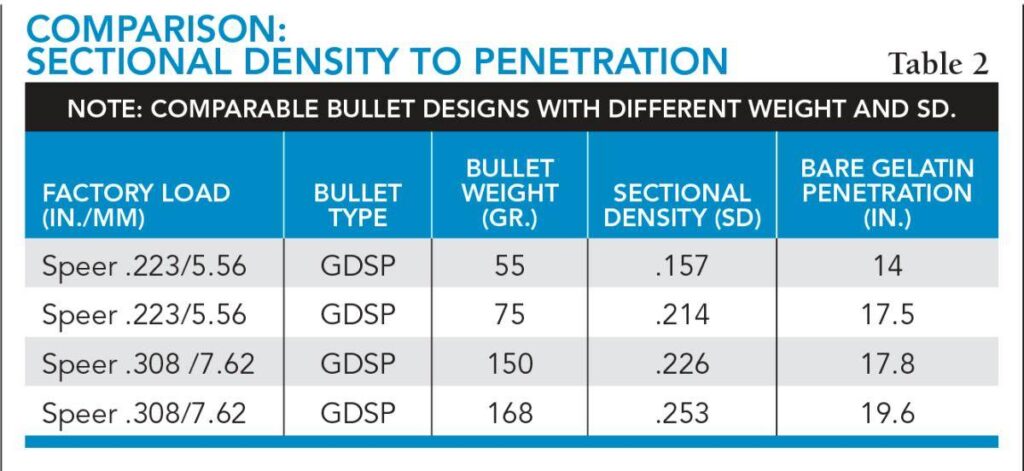

Table 2 shows the penetration of bullets with the same design but different SD in bare gelatin. This data is courtesy of Federal. As you can see for bullets of comparable design, an increase in SD positively correlates to weight and penetration.

Maximum Point-Blank Range (MPBR)

This is a term we haven’t heard mentioned much since the rush to “long-range” hunting. MPBR still has plenty of meaning to those that want to hunt at traditional ranges inside of 400 yards, and those using traditional, less expensive and smaller-objective scopes lacking target knobs. The definition of MPBR is a rifle zero with a specific ammunition load such that the trajectory of the bullet will not rise above or fall below the height of the kill zone of a particular animal. For this zero, the MPBR is the range at which the bullet falls below the lower limit of the kill zone.

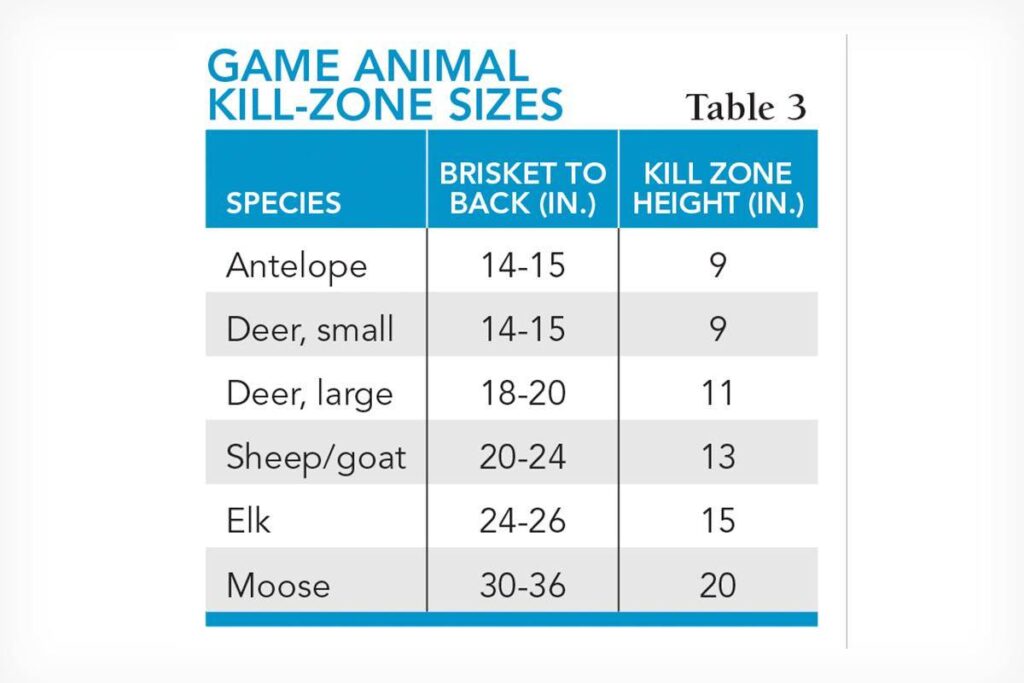

To explain this further, we need to discuss a little bit of animal physiology. As we all know, there are widely different sizes of game animals. The lungs and heart of an animal are the vulnerable organs, thus, it’s what hunters aim to hit. When an expanding bullet penetrates these organs, it will result in rapid incapacitation and a humane kill. Hence, this is the “kill zone” of an animal. Naturally, the size of the animal largely determines the size of the kill zone. Table 3 shows the generally accepted kill zone size for a number of common game animals. I would suggest that you not use the entire size of the kill zone to determine your gun’s zero and MPBR, though. My suggestion is that if you are going to set up your rifle for a zero corresponding to the kill zone size of a particular animal, you use no more than three-quarters of the kill-zone height. This gives you a little margin for a misplaced shot, and not all animals will fit into this chart.

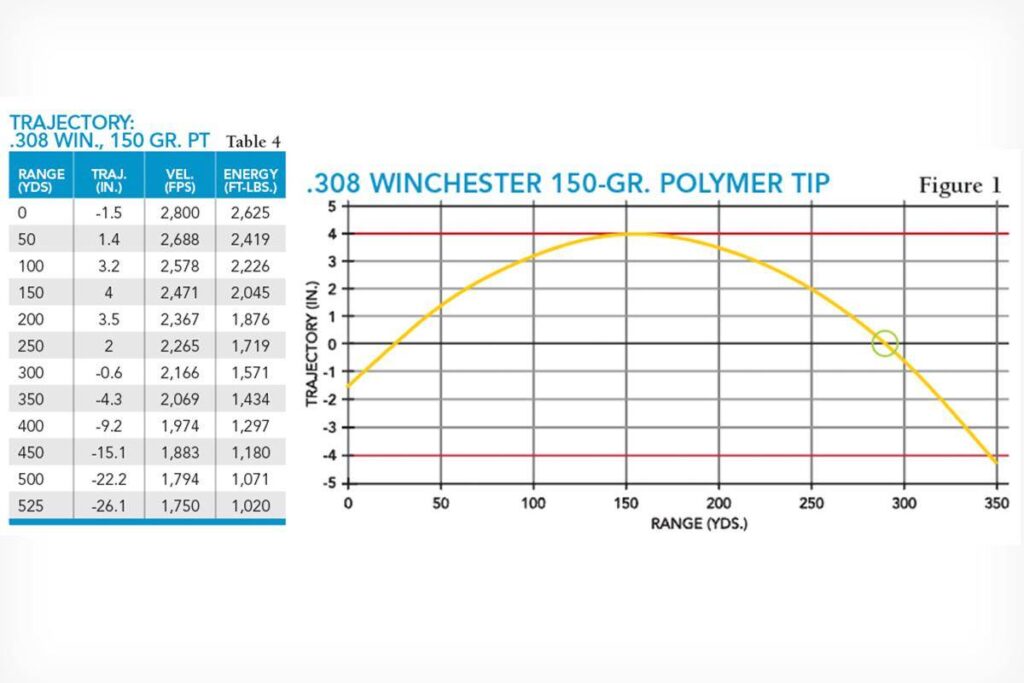

As an example, let’s say that you somehow manage to draw a mule deer tag in a western state. You decide you are going to take your favorite .308 Winchester loaded with a polymer-tipped 150-grain bullet fired at 2,800 fps. Looking at Table 3, you see the maximum kill-zone size for a large deer is 11 inches, so let’s use a kill-zone maximum height of 8 inches. Set the rifle up for a zero that gives a maximum trajectory height of 4 inches and then determine the range at which the bullet drops below 4 inches. The range at which it drops below 4 inches low is the MPBR. This range is the maximum range at which you could shoot at this large deer and not worry about the range or holdover. With a good shot, you’ll know that it will hit the kill zone, at least vertically. Left and right will be influenced by the wind and your ability to compensate for it. Table 4 shows the ballistics of this round, and Figure 1 is a graph of the trajectory with red lines drawn to show the limits of 4 inches high and low.

Seen in the graph, you would want to zero the rifle for about 290 yards for 4 inches maximum height of trajectory at 150 to 160 yards. This would correspond to being 3.2 inches high at 100 yards. This zero would give you an MPBR of about 345 yards, which is where the bullet drops below 4 inches.

Minimum Striking Energy (MSE)

I’m going to admit right up front that this topic and my opinions on it may raise a little controversy — but hear me out. The premise of MSE says that in order to ethically kill an animal you have to have a certain minimum amount of energy. That energy for an elk is said to be 1,500 foot-pounds (ft.-lbs.), and 1,000 ft.-lbs. for a deer. I believe MSE is a bit of a misnomer. At the business end of the bullet, striking the animal, it isn’t so much about the energy, but the striking velocity and what kind of expansion, wound cavity and penetration the bullet can produce at that striking velocity. MSE can be used as kind of a guide, but as I will show from our 150-grain .308 Win. load, this can be misleading as to what to expect. I am more inclined to look at the striking velocity of the bullet at a distance and have an idea of the minimum velocity your bullet of choice will provide useable expansion and produce enough terminal performance to cleanly take the animal. Using the MSE numbers can be misleading. Is anyone seriously going to argue that a .44 Magnum firing a 300-grain hollowpoint bullet with retained energy of 782 ft.-lbs. at 50 yards would not humanely kill a deer at that distance? You now see why I feel it is far more important to look at retained velocity and know the threshold velocity at which your bullet won’t produce expansion anymore. Table 5 lists some approximate velocities for expansion threshold for several different types of bullets.

Using the tipped 150-grain .308 Win. ballistics information, and playing it safe, say we want our bullet to strike our deer at a minimum of 1,900 fps? We can see that this would occur at a range of approximately 440 yards, plus or minus a little. If we were using the MSE criteria of 1,000 ft.-lbs., that would suggest we could push the range to about 535 yards. There’s a pretty big difference in those two distances. I would not expect our tipped 150-grain bullet, with a retained velocity of about 1,700 fps, to do much more than punch a small hole through the deer.

Learn Your Ammo

After reading this, I hope that you have a better understanding of ballistic considerations for hunting. You could certainly pay no attention to any of this, shoot ammunition out of the box and not worry about it. However, you could enhance your experience and find an online ballistic calculator. Then, try the techniques I described to fine tune your setup. Go out and shoot at different distances and prove to yourself that MPBR works. Research or call your favorite bullet manufacturer’s tech line and ask what the lower threshold for expansion is regarding your projectile. You’ll then know the maximum range you should be trying to use the bullet to. Doing this will give you a lot more confidence when it’s time to hunt. That confidence can make the difference between success and failure.

When selecting a deer cartridge, it’s helpful to keep it mainstream. Rifles chambered for 444 Marlin and 257 Roberts +P both excel at taking medium game. Unfortunately, less popular rounds like those also make it more difficult to source the steady supply of ammo you’ll need for target practice. You do want to thoroughly familiarize yourself with your rifle’s performance before you stake the outcome of a hunt on it, after all! Before committing to a new deer caliber, check to see how easily you can buy it at local gun shops and online. If you turn up a big fat goose egg during your initial search, then it’s reasonable to expect similar frustration in the future. That all said, we’re going to limit our recommendations to very popular cartridges.

When selecting a deer cartridge, it’s helpful to keep it mainstream. Rifles chambered for 444 Marlin and 257 Roberts +P both excel at taking medium game. Unfortunately, less popular rounds like those also make it more difficult to source the steady supply of ammo you’ll need for target practice. You do want to thoroughly familiarize yourself with your rifle’s performance before you stake the outcome of a hunt on it, after all! Before committing to a new deer caliber, check to see how easily you can buy it at local gun shops and online. If you turn up a big fat goose egg during your initial search, then it’s reasonable to expect similar frustration in the future. That all said, we’re going to limit our recommendations to very popular cartridges.