Tailor your choice of riflescope reticle—in the first or second focal plane—to your intended hunting pursuits.

Many hunters don’t understand riflescopes. A riflescope is not a sight. It contains the sight—the reticle—and provides magnification, eliminates parallax and allows for sight adjustment. But, the reticle within the riflescope is the actual sight; it’s what you use to aim. When hunters are considering a new scope, too often they overlook reticles or do not understand that they function differently depending on where they’re placed within the riflescope. With variable-powered scopes, the reticle is either placed in the front or the rear of the erector tube, and the erector tube is what allows for the riflescope’s magnification—zoom function—to be adjusted.

FIRST FOCAL PLANE

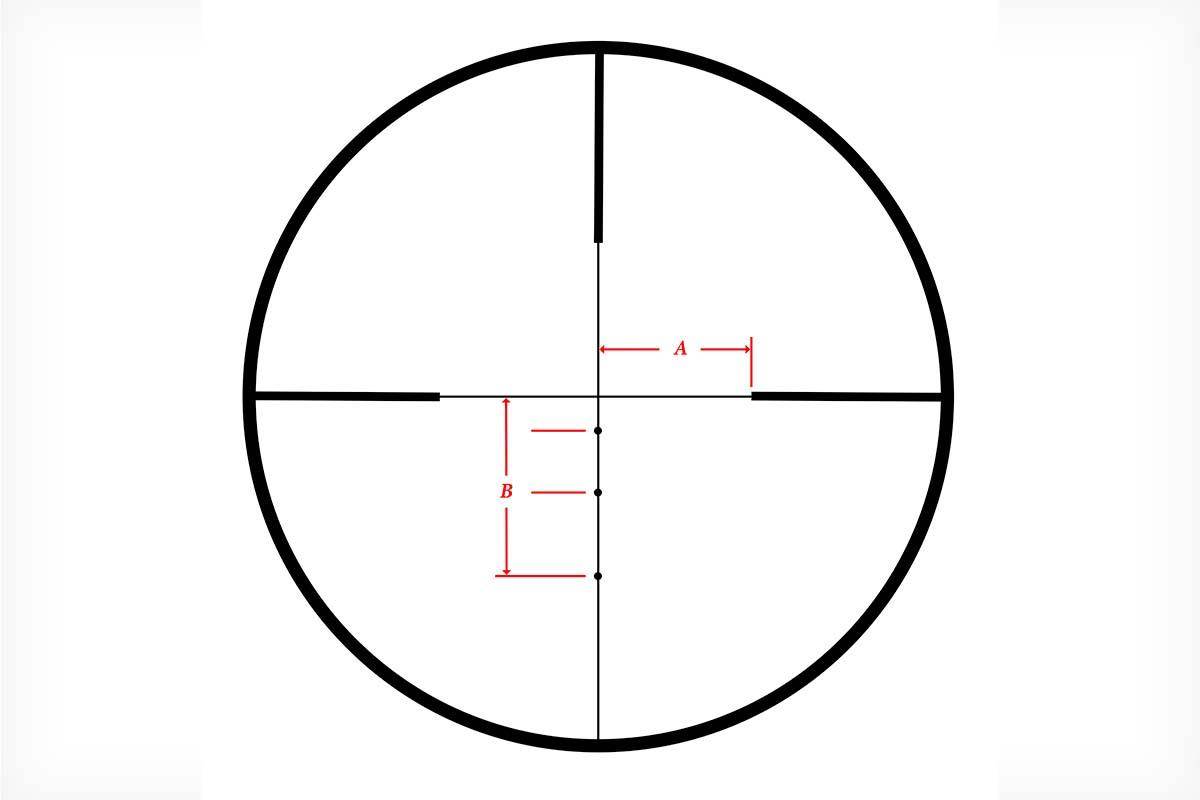

If the reticle is in front of the erector tube, when the riflescope’s magnification is increased, it not only magnifies the image but also the reticle. If you adjust magnification from 5X to 10X, the image and the reticle appear twice as large. Due to this, the subtensions of the reticle—its size in relation to the target—do not change with magnification. In the diagram below, subtensions A and B would remain the same no matter the magnification at which the riflescope is set.

SECOND FOCAL PLANE

If the riflescope’s reticle is at the rear of the erector tube, then the appearance of the reticle does not change as magnification is adjusted. This means the subtensions of the reticle—its size in relation to the view/target—do change with magnification. In Diagram 1, subtensions A and B would decrease by half with a magnification adjustment from 5X to 10X. Or they would double in size with a similar adjustment from 10X to 5X. This is simply because the image that you see through the riflescope is being magnified, whereas the reticle is not.

SOME HISTORY

For many years, scopes made in America or for the U.S. market were built with a rear or second-focal-plane reticle. But, European-made riflescopes were usually built with the reticle in the first focal plane. Most American hunters didn’t like how the reticle in European scopes increased in size when the magnification was adjusted. So, about two decades ago, many European optics companies began building second-focal-plane riflescopes to appeal to Americans.

With a ballistic reticle positioned in the second focal plane, the subtensions for that reticle were typically set to equal a standardized trajectory or a specific mil or MOA measurement only at a single magnification. This was usually the scope’s maximum magnification setting. Second-focal-plane scopes proved problematic in long-range shooting, specifically when the magnification needed to be adjusted due to mirage, distance or target size. When that happened, the subtensions of the reticle changed.

But, as long-range shooting became more popular in America—both for competition and hunting—so too did first-focal-plane reticles. This was because the subtensions of ballistic reticles—reticles with extra aiming points to match standardized trajectories, or with graduations in mils or MOA—positioned in the first focal plane do not change when magnification is adjusted. For example, if you need to make a 2-MOA correction with your reticle, the 2-MOA subtension always equals 2 MOA, no matter the riflescope’s magnification setting. If the second aiming point below the center of the reticle is your aiming point for a 400-yard shot, that aiming point can be used at that distance no matter the scope’s magnification setting.

WHAT’S BEST?

To answer this, first consider the type of hunting you’ll be doing. Except for varmint hunters who routinely shoot at extreme range, most hunters rarely shoot at animals beyond 300 yards. In fact, most shots—successful shots—at big-game animals are taken much closer. In those cases, ballistic reticles are of no real value. And, when a longer shot is required while hunting, you typically have time to adjust the magnification to maximum power to use a ballistic reticle in a second-focal-plane riflescope.

It’s also common for big-game hunters to be in situations where the maximum shot distance can be very close, such as when hunting thick timber. Here hunters will want to turn the magnification way down. That way, if they need to take a shot, the animal will be easier to locate and the sight—the reticle—will be easier to position over the correct spot. With the first-focal-plane reticle, this can become difficult, especially in instances where the light is dim.

The reason for this is the exact thing that makes a first-focal-plane reticle great for use at extreme range. For a reticle to be adequate for long-range shooting, it must not appear to be overly thick as it relates to the target. Otherwise, precise aiming becomes difficult. And remember, as the magnification of a first-focal-plane riflescope is adjusted, the image and the reticle are magnified. So, when a first-focal-plane riflescope is set to minimum magnification, the reticle must be very thin. Otherwise, when the magnification is increased, it will become too thick. This is especially true with riflescopes that have a broad magnification range.

At minimum magnification, the reticle in a first-focal-plane riflescope can be so thin that it is difficult to see. And the less light there is, the harder it is to see. If you must take a close shot in the darkness of the timber, you may not be able to clearly see the first-focal-plane reticle.

A first-focal-plane reticle might be nice if you often take long shots at big game. It may also be helpful if you’re a varmint or predator hunter where long shots are common, and you’re continually fine-tuning the magnification of your riflescope while hunting. Otherwise, a first-focal-plane reticle offers virtually no advantage to the hunter. For big-game hunters who like the first focal plane reticle’s consistent reticle subtensions, consider choosing one that’s illuminated—or that at least has an illuminated center dot. It’ll be much easier to see at low power and in low-light situations.